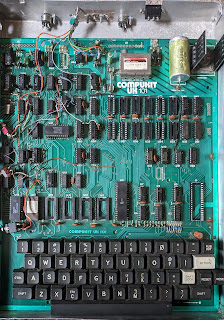

It seems like about two years ago, IC testers made quite a splash, judging by reviews of the Retro Chip Tester Pro (Adrian's Digital Basement) and the BackBit Chip Tester Pro (Noel's Retro Lab). Nice products though they are, they are a little out of my price range for this project.

TTL testing

Luckily for my wallet, there are several DIY projects out there which can be assembled from commonly-available parts in not too long. Nick Gammon (who's excellent interrupt and power-saving pages were inspiration for my Interrupted project) has a super-simple one which can be assembled on a breadboard in about an hour for the cost of 16 resistors, some dupont connectors and an Arduino Uno!

|

| It ain't pretty but it works! |

Nick credits an

Instructable by one "JorBi" for inspiration for his work. That project is more elaborate, using an Arduino Nano and a display --- Nick's just uses the Arduino serial port, nothing wrong with that. JorBi's project also provided the data file containing the actual chip tests: JorBi stores this in an EPROM while Nick puts it in the on-chip flash.

Another tester of note is the Smart-IC-Tester: an Arduino shield with TFT display. This stores the test database on an SD card, in a format very similar to JorBi's, just adding a one-line description to each part.

So? Well out of 34 74-series TTL chips on the UK101, Nick's tester flagged 7 as bad, 15 as good, 4 were unknown and 8 not tested, due to having wires soldered to them. Not bad for a day's work!

The bad chips were as follows:

- Two 74125s

- Three 74123s (all from the same batch)

- One 7403

- One 7404 (in bad shape, one pin broke off in the socket)

Note, it could be that the 74123 and 74125 tests are incorrect. I have none which tested good.

Update: After playing with the IC-Tester for a while longer, I managed to add tests for the hitherto-unknown chips. The latest score is 9 bad, 22 good and 3 not tested. My fork of Nick's repo is

here.

Update 2: I built this circuit on a piece of vero board and piggy-backed it onto my home-brew Uno!

|

| An improvement anyway! |

Memory testing

In addition to the discrete TTL chips, the UK101 also had 32 2114 static RAM for main memory and another 4 for the display. Nick's tester is unable to test this IC. Luckily somone named "skjerk" has

written a sketch for the Arduino Uno which does exactly this.

The 2114 has a pretty bad rep when it comes to living into old age so I didn't hold out much hope for my set. Rather incredibly however they all came up good!

Untested so far

Chips which I haven't been able to test yet:

- The 6502 and 6851

- The Basic ROMs and Character Generator ROM

- The monitor EPROM

Given an EPROM programmer, it should be possible to read the ROMs and compute their checksums. Stay tuned for that!

Of course the two commercial testers mentioned above can test all of these chips, out-of-the-box. But where's the fun in that?